Opioids and Depression: How Mood Changes Happen and How to Monitor Them

Dec, 5 2025

Dec, 5 2025

Opioid Depression Risk Calculator

Based on data from JAMA Psychiatry and CDC guidelines

Recommended monitoring:

Take the PHQ-9 assessment to screen for depression

Take Free PHQ-9 QuizWhen you take opioids for pain, you might expect relief - not a heavy, empty feeling that won’t go away. But for many people, the very drugs meant to ease physical suffering can quietly drag down their mood. Between 1 in 3 and more than half of those on long-term opioids for chronic pain also struggle with depression. And it’s not just coincidence. The connection runs deeper than you think - it’s wired into your brain chemistry.

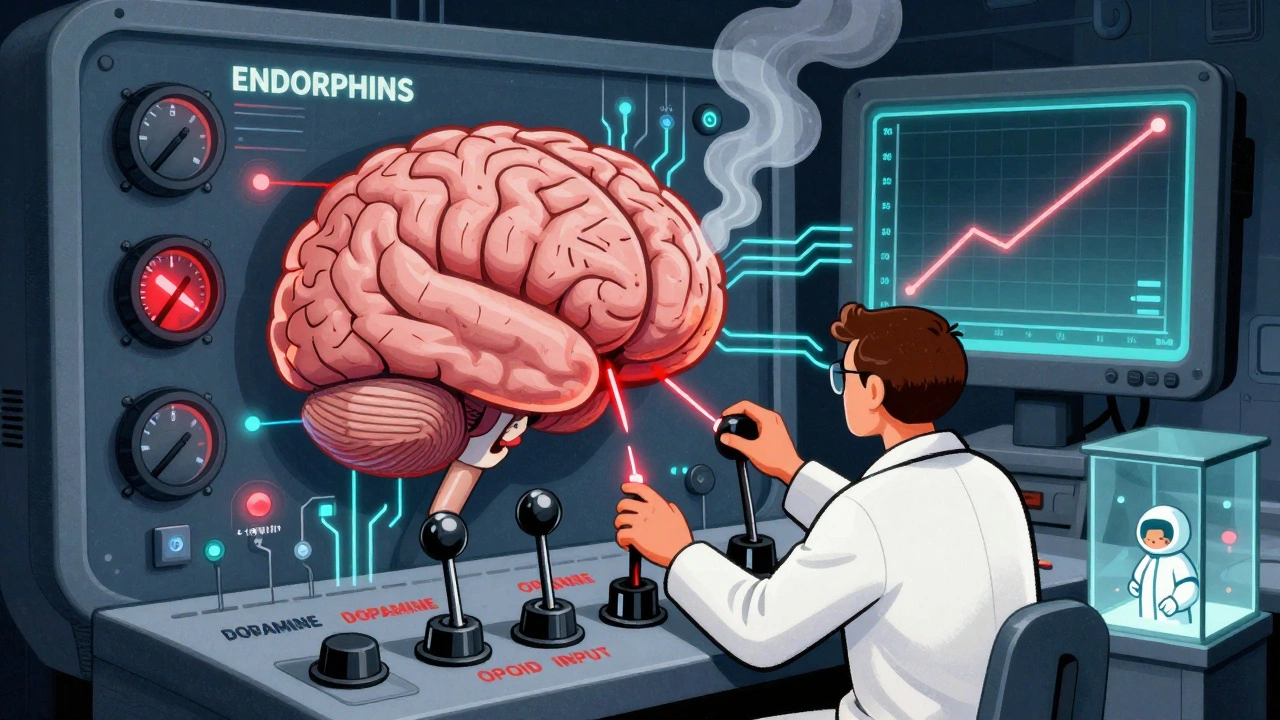

Why Opioids Can Make You Feel Worse, Not Better

Opioids work by binding to receptors in your brain that control pain, but those same receptors are also part of your emotional system. In the short term, this can feel like a double win: less pain, and maybe even a little lift in mood. Some people report feeling calmer or even mildly euphoric when they first start taking them. That’s not just in their head - studies on rodents show opioids like morphine and buprenorphine reduce signs of despair in lab tests by up to 60%.

But here’s the twist: what helps in the short term can hurt over time. Long-term use changes how your brain makes and uses its own natural painkillers and mood regulators. Your brain starts to rely on the drug to keep things balanced. When it doesn’t get enough, it doesn’t just hurt - it feels hollow. That’s when sadness, lack of interest, and emotional numbness creep in.

A 2020 genetics study in JAMA Psychiatry found that people with a genetic tendency to use prescription opioids were more likely to develop major depression - even when researchers controlled for other factors like chronic pain or stress. This suggests opioids themselves may be driving depression, not just being taken by people who are already depressed.

The Vicious Cycle: Pain, Opioids, and Depression

It’s easy to assume depression comes first - that someone with chronic pain gets sad, then gets prescribed opioids. But the data shows it’s a loop. People with depression are more likely to start opioids for pain, and once they’re on them, they’re twice as likely to become long-term users. And the more they take, the worse the depression gets.

One study of burn patients found that the total amount of opioids given over time directly correlated with higher depression scores. Another tracked over 34,000 people and found those using opioids weekly or daily were nearly twice as likely to develop depression compared to those using them rarely. Dose matters too: people taking more than 50 mg of morphine equivalent per day had more than three times the risk of depression compared to those not taking opioids at all.

And it’s not just about feeling sad. Depression in this context often shows up as anhedonia - the inability to feel pleasure in things you used to enjoy. You stop calling friends. You don’t care about hobbies. You feel stuck, even when the physical pain improves.

Why Doctors Often Miss It

Here’s the problem: depression in people on opioids is easy to overlook. Doctors focus on pain levels. Patients don’t always mention mood changes - they think it’s just part of living with chronic pain. Or they’re embarrassed. Or they assume it’ll go away once the pain is under control.

Studies show general practitioners catch only about half of depression cases in chronic pain patients. Even when guidelines from the CDC and the American Pain Society say to screen for depression before and during opioid therapy, only about 40% of primary care doctors do it consistently. A 2019 national survey found just 58% of providers routinely check for depression in these patients.

But skipping screening is dangerous. Depression doesn’t just make life harder - it makes opioid treatment riskier. People with untreated depression are more likely to take higher doses, misuse their meds, or have trouble sticking to treatment plans.

How to Monitor Mood Changes Properly

Monitoring isn’t just about asking, “Are you feeling down?” It needs structure. The most reliable tools are simple, validated questionnaires you can take in a few minutes.

- PHQ-9 - The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 asks about sleep, energy, appetite, concentration, and feelings of worthlessness over the past two weeks. Scores above 10 suggest moderate to severe depression.

- BDI - The Beck Depression Inventory gives a more detailed picture, especially for tracking changes over time.

Experts like Dr. Roger Weiss, who led the POATS trial, recommend screening every month for the first six months of opioid therapy, then every three months after that. That’s because depression symptoms often show up within three months of starting long-term use.

But numbers aren’t enough. Watch for behavioral signs too:

- Withdrawing from family or social events

- Stopping activities you used to love

- Changes in sleep or appetite that don’t match your pain levels

- Saying things like, “What’s the point?” or “I just want to sleep all day”

These aren’t signs of weakness. They’re red flags your brain is struggling.

What Can Be Done? Treatment That Works

There’s good news: treating depression doesn’t mean stopping opioids. It means treating both at the same time.

One study found that when people with chronic pain and depression got cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) along with their pain care, their opioid doses dropped by 32% on average. That’s because better mood means less perceived pain and less need for medication.

Even more surprising: a low dose of buprenorphine - the same drug used to treat opioid addiction - has shown antidepressant effects in people who haven’t responded to standard antidepressants. In one trial, patients with treatment-resistant depression saw major mood improvements within a week of taking just 1-2 mg daily. But here’s the catch: the FDA hasn’t approved buprenorphine for depression. So doctors can’t legally prescribe it for that reason alone - even if it helps.

That’s why integrated care matters. The best outcomes come from teams that include pain specialists, mental health providers, and pharmacists working together. If your doctor only talks about pills and doses, ask for a referral to a psychiatrist or therapist who understands chronic pain.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Now

The National Institutes of Health just gave $4.2 million to researchers at Columbia University to study exactly how opioids affect the brain’s mood circuits using brain scans. Another major study tracking 5,000 people with chronic pain and depression will run through 2026. These aren’t just academic projects - they’re trying to solve the biggest contradiction in this field: if opioids can lift mood in the short term, why do they cause depression over time?

The leading theory? Short-term use boosts mood by activating the brain’s reward system. Long-term use wears it out. The brain stops making its own opioids. It becomes hypersensitive to stress. And that’s when depression takes root.

Understanding this isn’t about scaring people away from opioids. It’s about using them smarter. If you’re on opioids for more than a few weeks, your mood matters as much as your pain level. Monitoring it isn’t optional - it’s part of safe, effective care.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re taking opioids:

- Take the PHQ-9 quiz online (it’s free and takes less than five minutes). Do it now, and again in three months.

- Write down any mood changes - even small ones - and bring them to your next appointment.

- Ask your doctor: “Have you screened me for depression? Can we do it today?”

- If you feel worse, not better, after starting opioids - don’t wait. Say something.

If you’re a caregiver or family member:

- Notice if your loved one stops talking, smiling, or doing things they used to enjoy.

- Don’t assume it’s just “the pain.” It might be the medicine.

- Encourage them to talk to their doctor - gently, but firmly.

Opioids aren’t the enemy. But ignoring their impact on mood is dangerous. The goal isn’t to avoid them entirely - it’s to use them with eyes wide open.

Can opioids cause depression even if I’m not addicted?

Yes. You don’t need to be addicted to experience depression from opioids. Studies show that even people taking prescribed opioids for legitimate pain, at therapeutic doses, have a higher risk of developing depression. The risk increases with longer use and higher doses, regardless of dependence or misuse.

How soon after starting opioids can depression appear?

Depression symptoms can emerge as early as three weeks after starting long-term opioid therapy. Research shows that 27% of patients on chronic opioids develop worsening depression within the first three months. That’s why monthly screening in the first six months is recommended.

Is it safe to stop opioids if I feel depressed?

Don’t stop abruptly. Stopping suddenly can cause withdrawal, which worsens mood and physical symptoms. Talk to your doctor. They can help you taper safely while addressing the depression with therapy, medication, or both. Often, treating the depression makes pain easier to manage - even without high opioid doses.

Can antidepressants help if I’m on opioids?

Yes, but not all work the same. SSRIs like sertraline or escitalopram are commonly used and generally safe with opioids. However, some antidepressants can interact with certain opioids, so your doctor needs to check for interactions. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is often more effective than medication alone for people with chronic pain and depression.

Why isn’t buprenorphine approved for depression if it helps?

Buprenorphine is approved only for opioid use disorder and pain. Even though studies show it lifts mood in treatment-resistant depression, the FDA hasn’t reviewed enough data for that specific use. Doctors can prescribe it off-label, but insurance rarely covers it for depression, and many providers are hesitant due to regulatory and stigma concerns.

What if my doctor says my depression is just from my pain?

That’s a common oversimplification. While pain can cause sadness, depression from opioids has distinct biological roots - including changes in brain chemistry that aren’t fixed by pain relief alone. If your mood doesn’t improve when your pain does, or if you feel numb even when you’re not in pain, that’s not just “being sad about pain.” It’s a medical issue that needs its own treatment.

What Comes Next

If you’re on opioids and feeling off - not just physically, but emotionally - you’re not alone. And you’re not weak. This is a known, measurable, treatable side effect. The next step isn’t guilt or fear. It’s action. Take the PHQ-9. Talk to your doctor. Ask for help. The goal isn’t to live without opioids - it’s to live well while using them.

Inna Borovik

December 7, 2025 AT 06:28Let’s be real - this article reads like a pharmaceutical industry PR pamphlet dressed up as science. Opioids don’t ‘cause’ depression - they expose it. People with untreated trauma, ADHD, or borderline personality disorder are prescribed opioids because doctors are lazy. Then when the mood crashes, they blame the drug. Classic victim-blaming with a side of medical gaslighting.

Jackie Petersen

December 8, 2025 AT 02:57Y’all really think Big Pharma didn’t engineer this? They knew opioids would hook people emotionally. That’s why they pushed them for chronic pain - not because it worked, but because it created lifelong customers. The FDA? Complicit. The CDC? Bought and paid for. This isn’t medicine - it’s a profit pipeline with a side of human wreckage.

Karen Mitchell

December 9, 2025 AT 02:40How can anyone in good conscience recommend opioids without mandatory psychiatric evaluation? This isn’t just negligence - it’s criminal. If your doctor doesn’t screen for depression before prescribing, you should report them. People are dying because providers think ‘pain management’ means ‘give more pills.’

Myles White

December 10, 2025 AT 18:22I’ve been on oxycodone for 8 years after a car accident. I didn’t realize my depression was tied to it until my therapist pointed out I hadn’t laughed at anything in 14 months. I started CBT, cut my dose by 40%, and now I’m hiking again. It’s not easy - but it’s possible. The article’s right: mood matters as much as pain. I wish someone had told me that five years ago.

Annie Gardiner

December 11, 2025 AT 10:06So we’re supposed to believe that a molecule can rewire your soul? Cute. But if opioids cause depression, why do so many people on them report feeling ‘normal’ for the first time? Maybe depression isn’t the side effect - maybe it’s the baseline. And opioids are just the only thing that lets you breathe. The real crime isn’t the drug - it’s a society that lets people suffer until they’re numb just to survive.

Akash Takyar

December 12, 2025 AT 02:20Thank you for this thoughtful, evidence-based overview. I appreciate how you emphasize structured monitoring - especially the PHQ-9. Many patients are unaware that mood changes are quantifiable, not ‘just in their head.’ I encourage everyone to take the quiz today, and to share the results with their provider. Small steps lead to meaningful change.

Kumar Shubhranshu

December 13, 2025 AT 14:19olive ashley

December 15, 2025 AT 03:11My mom’s been on fentanyl patches for 3 years. She used to paint. Now she stares at the wall. She says she’s ‘fine.’ But I know. I’ve seen it. The article’s right - it’s not the pain. It’s the pills. I begged her doctor to switch her. He said, ‘She’s stable.’ Stable? She hasn’t hugged me in 18 months.

Gwyneth Agnes

December 17, 2025 AT 02:36Kay Jolie

December 17, 2025 AT 19:11It’s fascinating how the neurobiology of mu-opioid receptor downregulation intersects with the mesolimbic dopamine pathway’s hypofunction in anhedonia - particularly in the nucleus accumbens shell. The epigenetic modulation of BDNF expression under chronic opioid exposure is a critical, underappreciated mechanism. And yet, we’re still relying on PHQ-9? We need fMRI-guided personalized interventions. This is 2024, not 2004.

Shayne Smith

December 18, 2025 AT 10:54I’m just here for the comments. This thread is wild. Like, I came for the opioids, stayed for the conspiracy theories and the emotional breakdowns. Someone get this guy a therapist.

Ibrahim Yakubu

December 19, 2025 AT 16:46Back home in Nigeria, we don’t have opioids for pain. We have traditional healers, prayers, and strong women who hold your hand when you cry. Maybe the problem isn’t the drug - maybe it’s a culture that treats bodies like machines and souls like afterthoughts. You don’t need a PHQ-9. You need someone who sees you.

Max Manoles

December 19, 2025 AT 20:34While the article correctly identifies the correlation between long-term opioid use and depression, it fails to adequately address confounding variables: pre-existing mental health conditions, socioeconomic stressors, and the psychosocial isolation that often accompanies chronic pain. The causal inference is overstated. Moreover, the recommendation to screen monthly is impractical in under-resourced primary care settings. A more nuanced, tiered approach is needed - one that balances clinical feasibility with patient safety.

Rashmi Gupta

December 20, 2025 AT 04:40They say opioids cause depression. But what if depression was already there - and opioids were the only thing that made it bearable? We act like people choose this. Like they’re weak. But when you’ve been in pain for years and no one believes you, sometimes the only thing that makes you feel human is a pill. Don’t shame us for needing it. Fix the system. Not us.