Why the First Generic Drug Filer Gets 180 Days of Market Exclusivity

Nov, 26 2025

Nov, 26 2025

When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the race to be the first generic company to file for approval isn’t just a business move-it’s a legal jackpot. The first company to submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with a Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell its version of the drug. No one else can enter the market during that time. That’s not a bonus. It’s a billion-dollar advantage.

How the 180-Day Clock Starts

This rule comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, a law designed to balance two things: protecting innovation and getting cheaper drugs to patients faster. The 180-day exclusivity isn’t automatic. It’s earned by being the first to file an ANDA that says, "This patent is invalid or I won’t break it." That’s a Paragraph IV certification. It’s a legal challenge. And it’s risky. If you lose the lawsuit, you get nothing.

The clock doesn’t start when the FDA approves the drug. It starts when the first filer either begins selling the generic or wins a court case saying the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed. That’s the twist. A company can win in court in January, sit on the approval, and not launch until June. But the exclusivity period still runs from January. That means no other generic can enter-even if the first filer hasn’t sold a single pill.

Why This Matters for Patients and Prices

Before Hatch-Waxman, generic drugs were rare. Brand companies held patents for years, and no one dared challenge them. The 180-day exclusivity changed that. It turned patent challenges into high-stakes investments. Companies like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz started spending millions on lawyers and scientists just to be first.

When the first generic hits the market, prices drop fast. In the first few months, the first filer often captures 70-80% of all sales. That’s because pharmacies and insurers prefer the cheapest option. And since no one else can compete yet, the first filer gets to set the price. Some generics have earned over $1 billion in those 180 days. Teva made $1.2 billion in exclusivity revenue on a generic version of Copaxone alone.

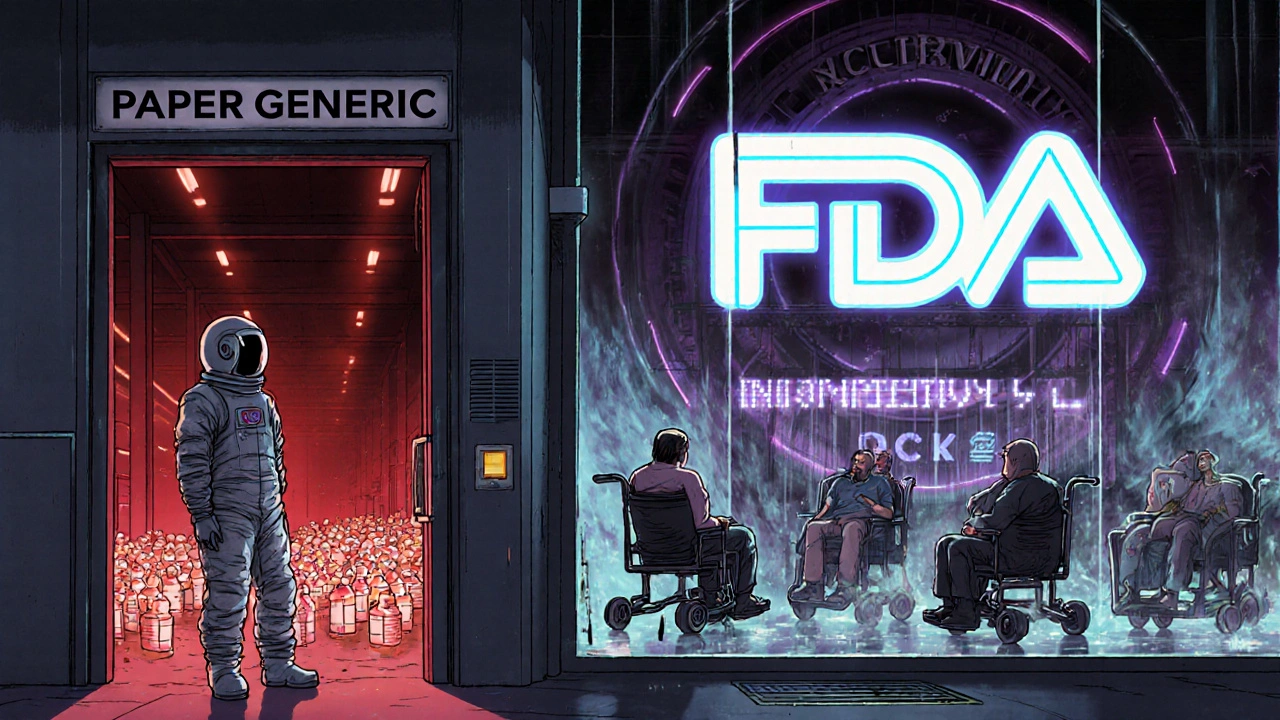

But here’s the problem: sometimes, the first filer never launches. They win the court case, sit tight, and block everyone else. This is called a "paper generic." The brand company doesn’t need to fight anymore. The market stays locked. A 2023 IQVIA report found that in 45% of cases where a Paragraph IV challenge was filed, the first applicant delayed or never launched-blocking competition for an average of 27 months.

The Dark Side: Reverse Payments and Authorized Generics

It gets worse. Sometimes, the brand company pays the first generic filer not to launch. These are called "reverse payments." The brand gives the generic a cut of the profits in exchange for staying off the market. The FTC estimates this costs U.S. consumers $3.5 billion a year.

Another tactic: the brand launches its own generic version during the exclusivity window. It’s called an "authorized generic." The brand sells the same pill, under a different label, at a lower price. The first filer still gets exclusivity, but now they’re competing against the very company they challenged. The brand wins. The first filer loses market share. The patient still pays more than they should.

In one 2022 Reddit post, a former brand executive admitted: "We’ve paid first filers up to $50 million not to launch for 18 months. It’s cheaper than losing 100% of our market share right away."

Why the System Is Broken

The FDA knew this would happen. That’s why, in 2022, they proposed a fix: the exclusivity period should only start when the first filer actually starts selling the drug. Not when they win a court case. Not when they get approval. When they put pills on the shelf.

Right now, the law lets companies game the system. They file early, win lawsuits, delay launch, and sit on exclusivity for years. The FDA’s current rules don’t stop that. In fact, they encourage it.

Meanwhile, small generic companies can’t compete. Filing a Paragraph IV challenge costs $5-10 million. It takes 18-24 months of legal and scientific work. Only big players like Teva or Viatris can afford it. That’s why 65% of these challenges come from just three companies-even though they make up only 35% of the generic market.

What’s Changing?

The FDA’s 2022 proposal would fix this. If passed, it would block other generics only after the first filer starts selling. That means no more paper generics. No more 27-month delays. Patients would get cheaper drugs faster.

But the brand drug industry is fighting back. PhRMA says changing the rule will hurt innovation. They argue that without the current system, no one will risk challenging patents. But the data says otherwise. Since Hatch-Waxman, 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are for generics. The system works. It just needs a reset.

What’s clear is that the 180-day exclusivity was meant to speed up access to affordable drugs-not delay it. The original goal was public health, not corporate profit. And right now, the system is failing that goal.

What You Can Do

As a patient, you can ask your pharmacist: "Is there a generic available?" If there is, but it’s still expensive, ask why. If no generic exists even after the patent expired, it’s likely because the first filer hasn’t launched-or was paid not to.

As a consumer, you can support policies that push for reform. The FDA’s proposed changes are simple: make exclusivity real. Make it start when the drug is sold, not when the paperwork is filed. That’s the only way to ensure the Hatch-Waxman Act delivers on its promise: lower prices, faster access, and real competition.

It’s not about big pharma vs. small generics. It’s about whether the law still serves patients-or just the players who learned how to bend it.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement filed by a generic drug company with the FDA, claiming that a patent on the brand-name drug is invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed by the generic version. It’s the only way a generic company can trigger the 180-day exclusivity period under the Hatch-Waxman Act.

Can more than one company get 180-day exclusivity?

Yes, if two or more companies file their ANDAs on the same day with valid Paragraph IV certifications, they can share the 180-day exclusivity. But if one company delays or forfeits exclusivity, the others can still enter the market. This is why timing matters-sometimes down to the second.

What happens if the first filer doesn’t launch?

Under current rules, if the first filer wins a court case but doesn’t launch, the 180-day clock still starts. No other generic can enter until the 180 days expire-even if the first filer never sells a pill. This loophole allows "paper generics" to block competition for years. The FDA wants to fix this by tying exclusivity to actual market entry.

How long does it take to file an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification?

Preparing a Paragraph IV challenge typically takes 18-24 months. It requires deep patent analysis, legal strategy, clinical data, and often litigation readiness. The cost ranges from $5 million to $10 million, which is why only large generic manufacturers can afford to play.

Is the 180-day exclusivity still useful today?

Yes-but only if it works as intended. Originally, it was meant to incentivize early challengers to bring down prices quickly. Today, it’s often used as a tool to delay competition. Reforming it to tie exclusivity to actual market entry would restore its original purpose and benefit patients.

Tiffany Fox

November 27, 2025 AT 04:36Rohini Paul

November 27, 2025 AT 10:46Natalie Sofer

November 28, 2025 AT 14:05Courtney Mintenko

November 30, 2025 AT 11:49Khamaile Shakeer

December 1, 2025 AT 16:10John Kang

December 1, 2025 AT 16:57Simran Mishra

December 2, 2025 AT 12:14Suryakant Godale

December 3, 2025 AT 04:38