How Liver and Kidney Changes in Older Adults Affect Drug Metabolism

Feb, 7 2026

Feb, 7 2026

When you're over 65, your body doesn't process medications the same way it did when you were younger. It’s not just about taking less - it’s about how your liver and kidneys have changed. These two organs are the main factories for breaking down and removing drugs from your body. As they slow down, what used to be a safe dose can become dangerous. This isn’t theoretical. About 1 in 10 hospital stays for people over 65 are caused by bad reactions to medications. And it’s not because they took too many pills - it’s because their bodies can’t handle the ones they’re on.

What Happens to the Liver as We Age?

Your liver shrinks. By the time you’re 80, it’s about 30% smaller than it was at 30. Blood flow to the liver drops by nearly 40%. That means drugs don’t get to the liver as quickly or as thoroughly. This affects how fast they’re broken down.

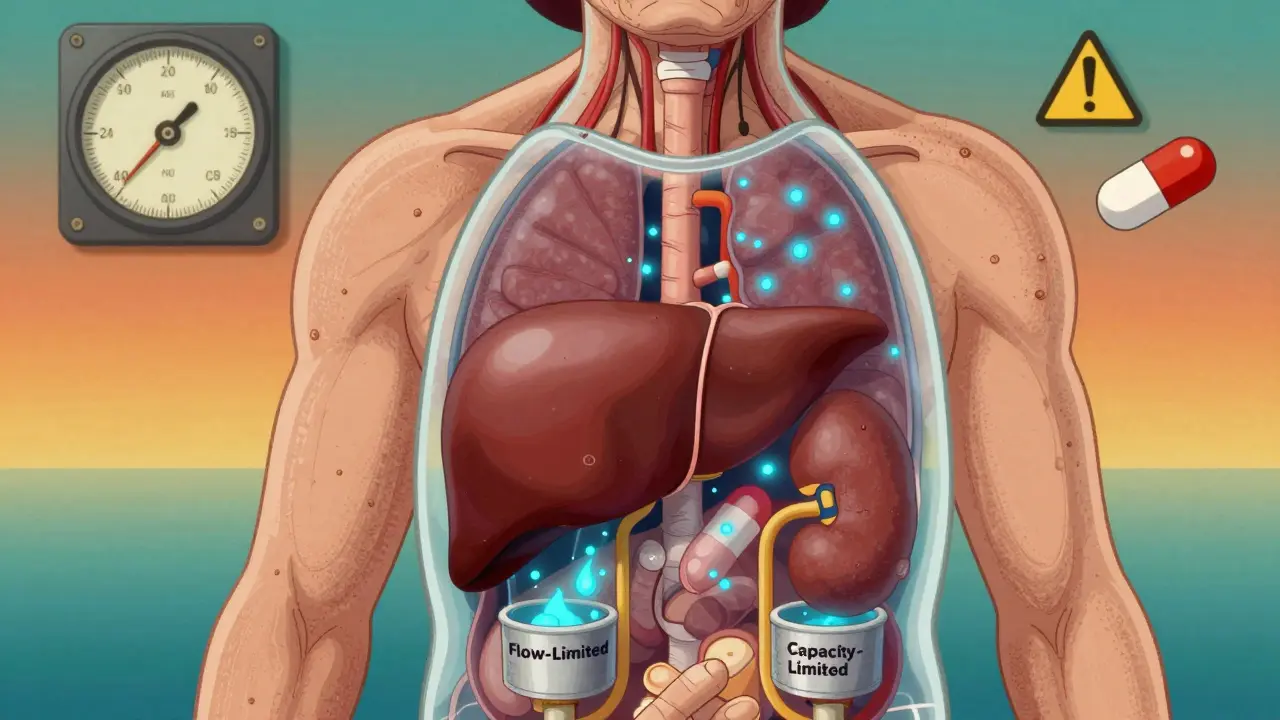

There are two types of drugs when it comes to liver processing. Flow-limited drugs - like propranolol, lidocaine, and morphine - depend on how much blood flows through the liver. When that flow drops, their clearance drops too. These drugs can build up in your system even if the dose hasn’t changed. That’s why someone on a standard dose of morphine might feel overly drowsy or dizzy.

Capacity-limited drugs - like diazepam, theophylline, and phenytoin - rely more on the liver’s enzymes. Here, the story is different. The enzymes themselves don’t decline as much as we once thought. Studies show their activity stays fairly steady. So these drugs may not need as big a dose reduction. But there’s a catch: some of these drugs are prodrugs, like perindopril. They need to be activated by the liver. If the liver is slower, the active form never reaches the right level. That means the drug doesn’t work as well - and your blood pressure might stay high, even though you’re taking your pill.

What Happens to the Kidneys?

The kidneys filter about 125 milliliters of blood per minute when you’re young. By age 80, that number often drops to 60-80 mL/min. That’s a 30-50% drop. But here’s the trick: your doctor might not know it. Serum creatinine - the blood test doctors use to check kidney function - stays normal because muscle mass declines with age. Less muscle = less creatinine. So the test looks fine, but your kidneys are actually working much harder just to keep up.

Drugs that leave the body through the kidneys - like digoxin, metformin, and many antibiotics - need lower doses. If they’re not adjusted, they pile up. Digoxin toxicity can cause irregular heartbeats. Metformin can lead to lactic acidosis. Both are serious. The Cockcroft-Gault formula has been the gold standard for calculating kidney clearance, but newer equations like CKD-EPI (without race adjustment) are now preferred because they’re more accurate for older adults.

Why Some Drugs Become Riskier

Not all drugs are created equal. Some are more dangerous in older adults because of how they’re handled. Take amitriptyline, an old antidepressant. It’s metabolized by the liver and cleared by the kidneys. In a 70-year-old, its half-life can double. That means it sticks around longer. One Reddit user, "CaregiverInMA," shared how their 82-year-old mother started on a standard 25 mg dose and ended up in the ER with severe dizziness and falls. The doctor later realized: her liver and kidneys couldn’t clear it. They cut the dose in half - and she stopped falling.

Even over-the-counter drugs can be risky. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is the #1 cause of accidental liver failure in older adults. Why? Because it’s processed by the liver, and many seniors take it daily for arthritis. Combine that with alcohol, dehydration, or other meds, and the liver gets overwhelmed. The Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity Registry shows 50% of acute liver failure cases in seniors come from routine acetaminophen use - not overdose.

How Doctors Adjust Doses - And Why They Don’t Always Get It Right

The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria® recommends starting seniors on 20-40% lower doses of liver-metabolized drugs. For those over 75, it’s often 50% lower. But here’s the problem: many doctors still use "one-size-fits-all" dosing. Why? Because they don’t test kidney or liver function properly. Or they assume age alone tells the whole story.

That’s why tools like the START/STOPP criteria matter. START helps doctors know what drugs to prescribe. STOPP helps them know what to avoid. A 2020 meta-analysis found that using these tools cuts adverse drug events by 22%. Yet most primary care practices still don’t use them routinely.

Another issue: drug interactions. Seniors often take five or more medications. The 2017-2018 NHANES survey found 41% of adults over 65 were on five or more prescriptions. That’s a recipe for trouble. One drug might slow down the liver’s ability to break down another. For example, fluconazole (an antifungal) can inhibit CYP3A4 - a key liver enzyme. If you’re taking simvastatin (a cholesterol drug) at the same time, your statin levels can spike, raising your risk of muscle damage.

New Tools Are Changing the Game

There’s hope. In 2023, the FDA approved GeroDose v2.1 - the first software designed to model how drugs behave in older bodies. You plug in age, weight, liver enzymes, and kidney function, and it predicts drug levels over time. It’s not perfect, but it’s a big step toward personalized dosing.

Researchers are also looking at epigenetics. A 2023 study found 17 specific DNA methylation sites that change with age and directly affect CYP3A4 activity. That means two 75-year-olds with the same kidney function might process drugs very differently. One might need half the dose. The other might be fine at the standard dose. This is the future: not just age, but biological age.

What You Can Do

- Ask your doctor: "Is this dose right for my liver and kidneys?" Don’t assume it is.

- Get a simple blood test: creatinine and eGFR. If your eGFR is under 60, ask if your meds need adjusting.

- Keep a list of every pill - including vitamins and OTCs. Bring it to every appointment.

- Be wary of "just one more" pill. Each new drug increases your risk.

- Don’t take acetaminophen daily without talking to your doctor. Use ibuprofen sparingly - it’s hard on kidneys.

There’s no magic number for how much to reduce a dose. It depends on the drug, your health, and your body. But one thing is clear: if you’re over 65 and on more than three medications, you should have this conversation - at least once a year.

Why This Matters Now More Than Ever

The global population over 65 will double by 2050. Right now, only 38% of drug trial participants are over 65. That means most of the dosing guidelines we follow were tested on people decades younger. We’re guessing. And guessing with medications in older adults can be deadly.

The U.S. spends $30 billion a year on hospitalizations from bad drug reactions in seniors. That’s money that could go to better care, better monitoring, better tools. But until we stop treating age as just a number - and start treating it as a biological factor - we’ll keep making the same mistakes.

It’s not about taking fewer pills. It’s about taking the right ones - at the right dose - for your body, not your birth year.

Marcus Jackson

February 8, 2026 AT 06:37Tola Adedipe

February 8, 2026 AT 12:24AMIT JINDAL

February 9, 2026 AT 16:50Natasha Bhala

February 11, 2026 AT 03:45Jesse Lord

February 13, 2026 AT 01:06Catherine Wybourne

February 14, 2026 AT 10:22Paula Sa

February 15, 2026 AT 22:18Mary Carroll Allen

February 16, 2026 AT 14:20Ritu Singh

February 16, 2026 AT 21:18Mark Harris

February 16, 2026 AT 22:27Mayank Dobhal

February 17, 2026 AT 07:26Ashley Hutchins

February 19, 2026 AT 06:40Lakisha Sarbah

February 19, 2026 AT 14:16Niel Amstrong Stein

February 20, 2026 AT 00:28Joey Gianvincenzi

February 20, 2026 AT 12:54